Exploratory Data Analysis

GEO 200CN - Quantitative Geography

Professor Noli Brazil

April 3, 2024

In last lab, you were introduced to the basics of R. In this lab, you will learn how to use R to run exploratory data analysis (EDA). The objectives of this lab are as follows:

- Learn how to run univariate descriptive statistics.

- Learn how to run bivariate descriptive statistics.

- Introduction to data visualization in R.

Installing and loading packages

As described in last lab, many functions are part of packages that are not preinstalled into R. In last lab, we installed the package tidyverse. We will be using one new package in this lab, so let’s install it.

install.packages("corrr")Installing a package does not mean its functions are accessible

during a given R session. You’ll need to load packages using the

function library(). Unlike installing, you need to use

library() every time you start an R session. A good

practice is to load all the packages you will be using in a given R

Markdown at the top of the file. We’ll be using the

tidyverse package in this lab, so let’s load it and the

corrr package in.

library(tidyverse)

library(corrr)Reading data

Let’s bring in some data to help illustrate EDA tools in R. I

uploaded a file on GitHub containing the number of Hispanic, white,

Asian, and black residents in 2018 in California neighborhoods taken

from the United States American Community

Survey. The data are also located on Canvas in the Lab and

Assignments Week 1 folder. To import this file in R, use the

read_csv() command, which is a part of the

tidyverse package.

neighborhoods <- read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/geo200cn/data/master/week2data.csv")The data object neighborhoods should have appeared in your environment window.

Let’s bring in another dataset containing some health and air

pollution data from California’s CalEnviroScreen

program. Read it in from GitHub using our new friend

read_csv().

ces <- read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/geo200cn/data/master/ces.csv")

names(ces)The dataset contains the poverty rate, air pollution levels (PM2.5), and whether the neighborhood is environmentally disadvantaged according to the CES.

Note the underscore in between read and

csv. There is a base R function called

read.csv(). What is the difference? The function

read.csv() stores your data into a regular data frame. The

function read_csv() stores your data in a special tidy R

object - a tibble.

Although the tidyverse works with all data objects,

its fundamental object type is the tibble. Tibbles are essentially a

special variant of data

frames that have desirable properties for printing and joining. An

important difference between tidy and base R is that

read_csv() will always read variables containing text as

character variables. In contrast, the base R function

read.csv() will sometimes convert a character variable to a

factor. Tidy R figures that if you really wanted a factor, you can

easily convert it when you load it in. read_csv() will also

not convert numbers with a leading zero into an integer. It figures that

if you want to convert it into an integer, you can do it after the data

are read in. In contrast, read.csv() will assume you want

it in an integer.

Data Wrangling

It is rare that the data you download is in exactly the right form

for analysis. For example, you might want to analyze just Yolo county

neighborhoods. Or you might want to discard certain variables from the

dataset to reduce clutter. Or you encounter missing data. The process of

gathering data in its raw form and molding it into a form that is

suitable for its end use is known as data wrangling. In this

lab, we won’t go through the various data wrangling functions that

tidyverse offers since all the data we will provide in

labs and assignments will be largely cleaned and ready for analysis. If

you would like to learn on your own, I’ve provided an extra lab on data

wrangling. You can also look through chapters 5 and 9-16 in R for Data Science.

However, I want to cover one of the most important innovations from

tidyverse, the pipe operator %>%,

before starting EDA.

Pipes are the workhorse of tidy analyses. Piping allows you to chain together many functions, eliminating the need to define multiple intermediate objects to use as the input to subsequent functions. Pipes are also the primary reason that tidyverse code is fundamentally easier to read than base R code.

It may seem complicated at first, but what the pipe does is actually quite simple. That is, it allows users to write linear code. To illustrate the use of the pipe, consider the following base R code that takes the mean of the log of three numbers

mean(log(c(1, 3, 9)))## [1] 1.098612Notice how the numbers c(1, 3, 9) are nested inside

log(), which is then nested inside mean(). If

you’re reading the code from left-to-right, it means the functions are

performed in reverse order from how they are written. If we broke the

code down into its three functions, we would actually expect the order

of operations to proceed as follows

- Concatenate numbers into vector

c(...) - Log the numeric vector

log(...) - Estimate the mean of the logged numeric vector

mean(...)

Now consider how you would do this using pipes.

c(1, 3, 9) %>%

log() %>%

mean()## [1] 1.098612In contrast to the nested base code, the tidy code is linear; in other words, the code appears in the same order (moving from left to right) as the operations are performed.

Let’s use pipes to conduct the following data wrangling tasks on the data object neighborhoods.

- rename the variable NAME to County

- keep all variables except nhasn

- create the percent race/ethnicity and majority Hispanic variables

- join the ces file

neighces <- neighborhoods %>%

rename(County = NAME) %>%

select(GEOID, County, hisp, nhblk, nhwhite, tpopr) %>%

mutate(pwhite = nhwhite/tpopr, phisp = hisp/tpopr,

pblk = nhblk/tpopr,

mhisp = ifelse(phisp > 0.5, "Majority","Not Majority")) %>%

left_join(ces, by = "GEOID")In the code above, the tibble neighborhoods is piped into

the command rename(). This command changes NAME to

County. The resulting object gets piped into the command

select(), which keeps the variables GEOID,

County, hisp, nhblk, nhwhite,

tpopr. This result gets piped into the mutate()

function, which creates the variables pwhite, phisp,

and pblk, which represent the proportion of the population that

is white, Hispanic and Black, and mhisp, which designates

neighborhoods as “Majority” Hispanic if its proportion Hispanic is

greater than 0.5, and “Not Majority” otherwise. This then gets piped in

the left_join() function, which joins the ces

dataset using the ID GEOID which uniquely identifies each

neighborhood.

Piping makes code clearer, and simultaneously gets rid of the need to define any intermediate objects that you would have needed to keep track of while reading the code.

Exploratory Data Analysis

Below we go through several methods for conducting Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA). We first start with univariate and bivariate statistics. We then go through how to construct charts and graphs.

Univariate statistics

Univariate statistics provide summaries of a single variable. The most common statistics capture a distribution’s central tendency or spread.

Central tendency

The most common univariate statistics are those that measure central

tendency. The most common measure of central tendency is the mean. We

can calculate the mean of a variable using the function **tidyverse*

function summarize().

summarize(neighces, mean(PM2.5))## # A tibble: 1 × 1

## `mean(PM2.5)`

## <dbl>

## 1 10.4The first argument inside summarize() is the data object

neighces and the second argument is the function calculating

the specific summary statistic, in this case mean(), which

unsurprisingly calculates the mean of the variable you indicate in

between the parentheses.

Other common measures of central tendency are the median (50th percentile)

summarize(neighces,

median(PM2.5))## # A tibble: 1 × 1

## `median(PM2.5)`

## <dbl>

## 1 10.4and the mode (most frequent value). There is no base function for

calculating the mode, so lets create our own function called

getmode().

# Create a function that calculates the statistical mode

getmode <- function(v) {

uniqv <- unique(v)

uniqv[which.max(tabulate(match(v, uniqv)))]

}We can plug in all three measures within a single

summarize().

neighces %>%

summarize(Mean = mean(PM2.5),

Median = median(PM2.5),

Mode = getmode(PM2.5))## # A tibble: 1 × 3

## Mean Median Mode

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 10.4 10.4 12.0The mean and the mode have the same value. What does this say about the shape of the distribution of PM 2.5?

Spread

The other common set of univariate statistics measure a

distribution’s spread. The three most common measures of spread are the

variance, its buddy the standard deviation and the Interquartile Range

(IQR). We calculate the variance, standard deviation and IQR using the

functions var(), sd() and IQR(),

respectively. Let’s combine them with measures of central tendency into

a single summarize().

neighces %>%

summarize(Mean = mean(PM2.5),

Median = median(PM2.5),

Mode = getmode(PM2.5),

Variance = var(PM2.5),

SD = sd(PM2.5),

IQR = IQR(PM2.5))## # A tibble: 1 × 6

## Mean Median Mode Variance SD IQR

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 10.4 10.4 12.0 6.74 2.60 3.35You can get a summary of all the variables in a data frame using the

summary() function.

summary(neighces)## GEOID County hisp nhblk

## Min. :6.001e+09 Length:7937 Min. : 0 Min. : 0.0

## 1st Qu.:6.037e+09 Class :character 1st Qu.: 641 1st Qu.: 34.0

## Median :6.059e+09 Mode :character Median : 1420 Median : 116.0

## Mean :6.055e+09 Mean : 1909 Mean : 269.5

## 3rd Qu.:6.073e+09 3rd Qu.: 2789 3rd Qu.: 311.0

## Max. :6.115e+09 Max. :14894 Max. :5469.0

## nhwhite tpopr pwhite phisp

## Min. : 0 Min. : 66 Min. :0.0000 Min. :0.0000

## 1st Qu.: 649 1st Qu.: 3495 1st Qu.:0.1466 1st Qu.:0.1537

## Median : 1590 Median : 4632 Median :0.3783 Median :0.3088

## Mean : 1839 Mean : 4904 Mean :0.3895 Mean :0.3797

## 3rd Qu.: 2681 3rd Qu.: 5924 3rd Qu.:0.6131 3rd Qu.:0.5805

## Max. :22842 Max. :38932 Max. :0.9804 Max. :1.0000

## pblk mhisp Poverty PM2.5

## Min. :0.000000 Length:7937 Min. : 0.0 Min. : 1.651

## 1st Qu.:0.008253 Class :character 1st Qu.:19.2 1st Qu.: 8.698

## Median :0.025617 Mode :character Median :33.5 Median :10.370

## Mean :0.055452 Mean :36.4 Mean :10.377

## 3rd Qu.:0.065583 3rd Qu.:51.6 3rd Qu.:12.050

## Max. :0.839158 Max. :96.2 Max. :19.600

## disadvantage

## Length:7937

## Class :character

## Mode :character

##

##

## You’ll notice that some variables are not given summary statistics. These are of class character. How do we summarize variables whose values are of class character?

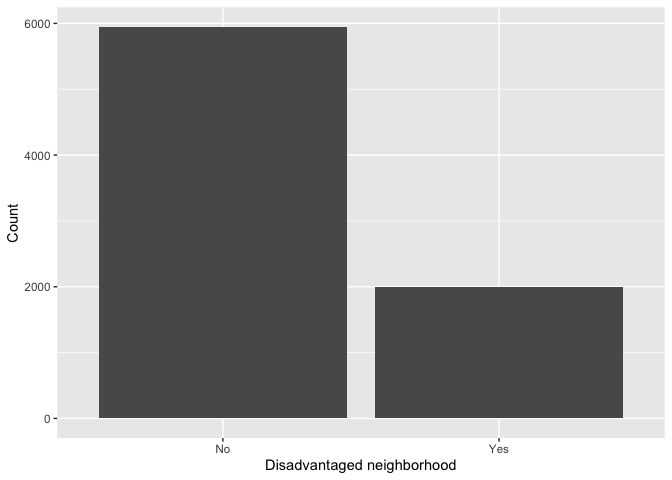

Categorical variable

You summarize a categorical variable using a frequency table. What

are the percentages of neighborhoods that are considered to be

environmentally burdened in California? To get these percentages, you’ll

need to combine the functions group_by(),

summarize() and mutate() using

%>%.

neighces %>%

group_by(disadvantage) %>%

summarize(n = n()) %>%

mutate(freq = n / sum(n))## # A tibble: 2 × 3

## disadvantage n freq

## <chr> <int> <dbl>

## 1 No 5947 0.749

## 2 Yes 1990 0.251The group_by() function applies another function

independently within groups of observations (where the groups are

specified by a categorical variable in your data frame). In the code

above, we group by whether neighborhoods are considered to be

disadvantaged or not. We used summarize() to count the

number of neighborhoods by disadvantage designation. The function to get

a count is n(), and we saved this count in a variable named

n. The code within mutate() calculates the

frequencies.

Bivariate statistics

A frequent goal in data analysis is to efficiently describe or measure the strength of relationships between variables, or to detect associations between categorical variables used to set up a cross tabulation. A related goal may be to determine which variables are related in a predictive sense to a particular outcome variable, or put another way, to learn how best to predict future values of a outcome variable. Correlation, along with measures of association constructed from tables, provide the means for constructing and displaying such relationships.

The correlation coefficient is used to measure the association

between two numeric variables. Use the function cor in R.

What is the correlation between PM2.5 levels and percent Hispanic? What

about percent White?

neighces %>%

summarize(hispcor = cor(phisp,PM2.5, use = "complete.obs"),

whitecor = cor(pwhite,PM2.5, use = "complete.obs"))## # A tibble: 1 × 2

## hispcor whitecor

## <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.366 -0.372You can obtain a correlation matrix to show bivariate correlation

across multiple variables. One way of doing this in R is to use the

correlate() function, which is found in the package

corrr.

neighces %>%

select(pwhite, phisp, pblk, Poverty, `PM2.5`) %>%

correlate()## # A tibble: 5 × 6

## term pwhite phisp pblk Poverty PM2.5

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 pwhite NA -0.771 -0.329 -0.598 -0.372

## 2 phisp -0.771 NA 0.0326 0.701 0.366

## 3 pblk -0.329 0.0326 NA 0.223 0.0766

## 4 Poverty -0.598 0.701 0.223 NA 0.234

## 5 PM2.5 -0.372 0.366 0.0766 0.234 NATo summarize the relationship between two categorical variables,

you’ll need to find the proportion of observations for each combination,

also known as a cross tabulation. Let’s create a cross tabulation of the

categorical variables mhisp and disadvantage. We do

this by using both variables in the group_by() command.

neighces %>%

group_by(disadvantage, mhisp) %>%

summarize(n = n()) %>%

mutate(freq = n / sum(n))## # A tibble: 4 × 4

## # Groups: disadvantage [2]

## disadvantage mhisp n freq

## <chr> <chr> <int> <dbl>

## 1 No Majority 980 0.165

## 2 No Not Majority 4967 0.835

## 3 Yes Majority 1492 0.750

## 4 Yes Not Majority 498 0.250A much higher proportion of disadvantaged neighborhoods are Majority Hispanic (0.750) compared to non disadvantage neighborhoods (0.165).

What about summarizing the relationship between a categorical and numeric variable? A typical way of summarizing the relationship between a categorical variable and a numeric variable is to take the mean of the numeric variable for each level of the categorical variable. What is the mean pollution levels for majority vs non-majority Hispanic neighborhoods?

neighces %>%

group_by(mhisp) %>%

summarize(Mean = mean(PM2.5))## # A tibble: 2 × 2

## mhisp Mean

## <chr> <dbl>

## 1 Majority 11.6

## 2 Not Majority 9.82You can also find the mean PM2.5 levels by county using the same code.

neighces %>%

group_by(County) %>%

summarize(Mean = mean(PM2.5)) ## # A tibble: 58 × 2

## County Mean

## <chr> <dbl>

## 1 Alameda 8.78

## 2 Alpine 2.59

## 3 Amador 6.65

## 4 Butte 9.05

## 5 Calaveras 6.26

## 6 Colusa 7.24

## 7 Contra Costa 8.01

## 8 Del Norte 3.80

## 9 El Dorado 6.78

## 10 Fresno 15.2

## # ℹ 48 more rowsHow can you add to the above code to find out the top 10 counties in average PM2.5 levels?

Data visualization

Instead of tables and summary statistics, you might want to summarize

your data using plots. The base R function for plotting is

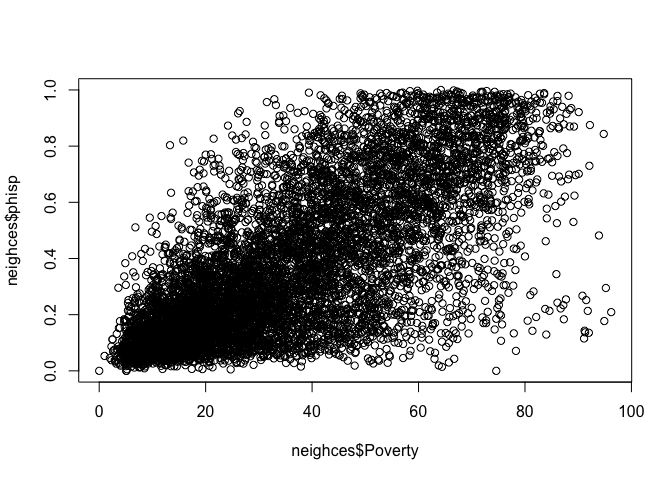

plot(). We can create a scatterplot (more on this later) of

proportion and Hispanic and the poverty rate by typing in the

following

plot(neighces$phisp~neighces$Poverty)

The tidyverse’s data visualization package is

ggplot2. The graphing function is ggplot()

and it takes on the basic template

ggplot(data = <DATA>) +

<GEOM_FUNCTION>(mapping = aes(x, y)) +

<OPTIONS>()ggplot()is the base function where you specify your dataset using thedata = <DATA>argument.You then need to build on this base by using the plus operator

+and<GEOM_FUNCTION>()where<GEOM_FUNCTION>()is a unique function indicating the type of graph you want to plot. Each unique function has its unique set of mapping arguments which you specify using themapping = aes()argument. Charts and graphs have an x-axis, y-axis, or both. Check this ggplot cheat sheet for all possible geoms.<OPTIONS>()are a set of functions you can specify to change the look of the graph, for example relabeling the axes or adding a title.

The basic idea is that a ggplot graphic layers geometric objects (circles, lines, etc), themes, and scales on top of data.

You first start out with the base layer. It represents the empty

ggplot layer defined by the ggplot() function.

ggplot(neighces)

We haven’t told ggplot() what type of geometric

object(s) we want to plot, nor how the variables should be mapped to the

geometric objects, so we just have a blank plot. We have geoms to paint

the blank canvas.

From here, we add a “geom” layer to the ggplot object. Layers are

added to ggplot objects using +, instead of

%>%, since you are not explicitly piping an object into

each subsequent layer, but adding layers on top of one another. Each

geom is associated with a specific type of graph.

Histogram

Histograms are used to summarize a single numeric variable. To create

a histogram, use geom_histogram() for

<GEOM_FUNCTION()>. Let’s create a histogram of PM

2.5.

ggplot(neighces) +

geom_histogram(mapping = aes(x=PM2.5)) +

xlab("PM 2.5")

Because a single variable is plotted on the x-axis, we specify

x = in aes() but not a y =. The

xlab() function, which is an example of a

<OPTIONS>() function, allows you to relabel the title

of the x-axis (ylab() is for the y-axis). The message

before the plot tells us that we can use the bins =

argument to change the number of bins used to produce the histogram. You

can increase the number of bins to make the bins narrower and thus get a

finer grain of detail. Or you can decrease the number of bins to get a

broader visual summary of the shape of the variable’s distribution. Try

changing the number of bins and see what you get.

Density plot

A density plot is a plot of the local relative frequency or density

of points along the number line or x-axis of a plot. The local density

is determined by summing the individual “kernel” densities for each

point. Where points occur more frequently, this sum, and consequently

the local density, will be greater. Density plots get around some of the

problems that histograms have. geom_density() is the

associated <GEOM_FUNCTION()> for a density plot.

Let’s make a density plot of PM 2.5.

ggplot(neighces) +

geom_density(mapping = aes(x=PM2.5)) +

ylab("PM 2.5")

Plots with both a histogram and density line can be created:

ggplot(neighces, aes(x=PM2.5)) +

geom_histogram(aes(y=..density..), colour="black", fill="white")+

geom_density(alpha=.2, fill="blue")

alpha = controls the transparency and

fill = controls for the color of the plot.

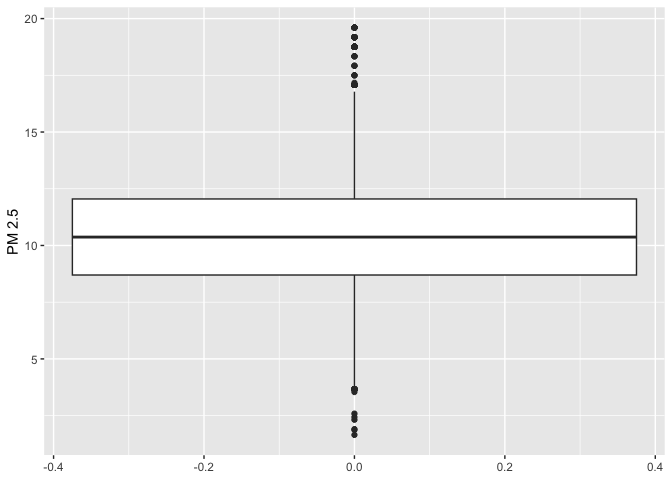

Boxplot

We can use a boxplot (or a box-and-whisker plot) to visually

summarize the distribution of a single numeric variable. Use

geom_boxplot() for <GEOM_FUNCTION()> to

create a boxplot. Let’s examine PM 2.5

ggplot(neighces) +

geom_boxplot(mapping = aes(y=PM2.5)) +

ylab("PM 2.5")

The top, middle and bottom of the box represent the 75th, 50th, and 25th percentiles, respectively. The points outside the whiskers represent outliers. Outliers are defined as having values that are either larger than the 75th percentile plus 1.5 times the IQR or smaller than the 25th percentile minus 1.5 times the IQR.

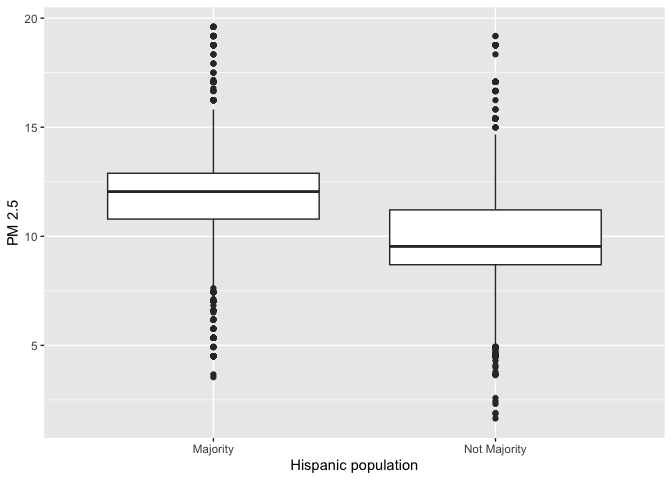

We can also use the boxplot to examine the relationship between a

categorical and numeric variable. Let’s examine the distribution of PM

2.5 by majority vs. non majority Hispanic. Because we are examining the

association between two variables, we need to specify x and

y variables within aes()

ggplot(neighces) +

geom_boxplot(mapping = aes(x = mhisp, y=PM2.5)) +

ylab("PM 2.5") +

xlab("Hispanic population")

Barchart

We use a bar chart to summarize a categorical variable. Bar charts

show either the number or frequency of each category. To create a bar

chart, use geom_bar() for

<GEOM_FUNCTION>(). Let’s show a bar chart of

environmentally disadvantaged communities.

ggplot(neighces, aes(x=factor(disadvantage)))+

geom_bar(stat="count")+

xlab("Disadvantaged neighborhood") +

ylab("Count")

This provides the number of observations in each category. What if we

want to get the percentage? There is no stat = "freq"

option, so we can borrow from the code we used earlier to create our

disadvantage frequency table and pipe this table directly into

ggplot().

neighces %>%

group_by(disadvantage) %>%

summarize(n = n()) %>%

mutate(freq = n / sum(n)) %>%

ggplot() +

geom_bar(mapping=aes(x=disadvantage, y=freq),stat="identity") +

xlab("Disadvantaged neighborhood") +

ylab("Proportion")

We didn’t need to specify data = <DATA> in

ggplot() because it was piped in. Within

aes(), we specified the categorical variable

disadvantage on the x-axis and then the proportion of

neighborhoods freq on the y-axis. The argument

stat = "identity" tells ggplot() to plot the

exact value listed for the variable freq.

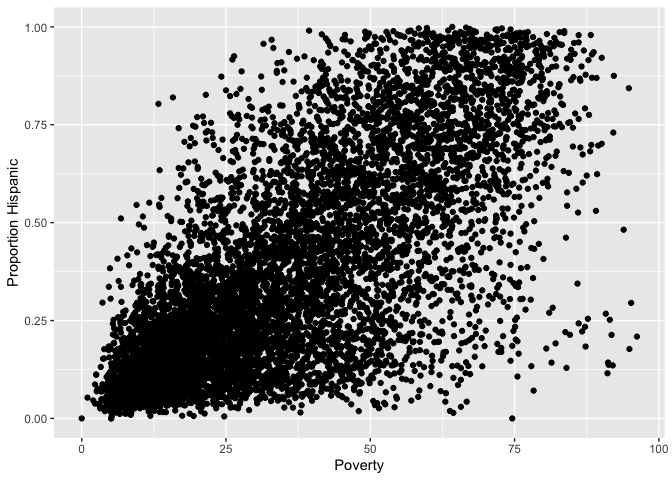

Scatterplot

The scatterplot is the traditional graph for visualizing the

association between two numeric variables. For scatterplots, we use

geom_point() for <GEOM_FUNCTION>().

Because we are plotting two variables, we specify an x and

y variable. Does proportion Hispanic change with greater

poverty in the neighborhood?

ggplot(neighces) +

geom_point(mapping = aes(x = Poverty,

y = phisp)) +

xlab("Poverty") +

ylab("Proportion Hispanic")

What does scatter plot suggest about the relationship between the two variables?

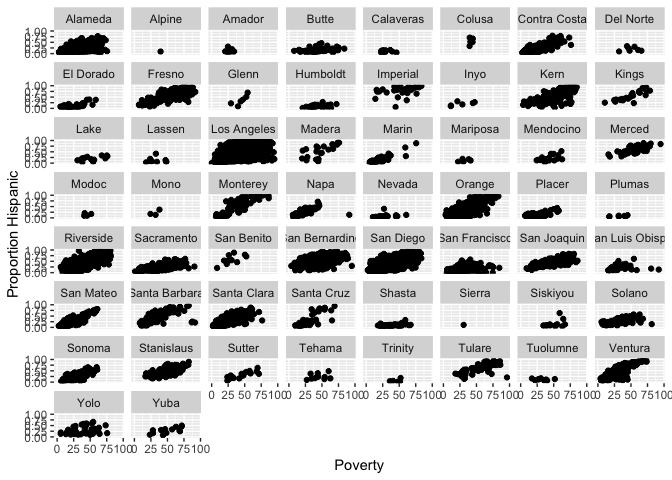

You can add the facet_wrap() function to create a

scatterplot for each county.

ggplot(neighces) +

geom_point(mapping = aes(x = Poverty,

y = phisp)) +

xlab("Poverty") +

ylab("Proportion Hispanic") +

facet_wrap(~County)

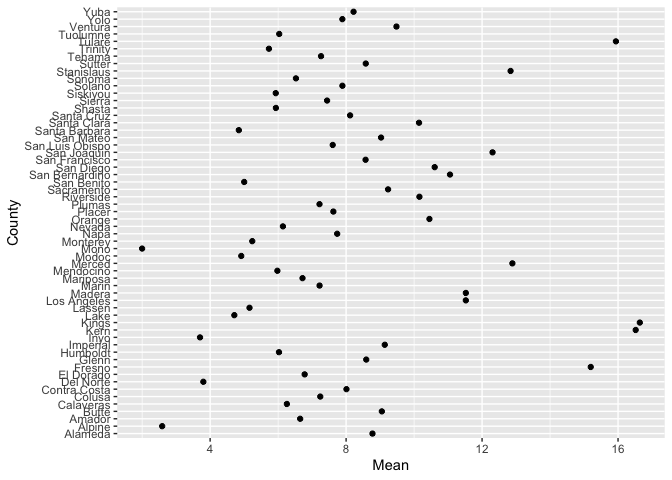

Dot plot

A (Cleveland) dot plot displays the values of a single variable as

symbols plotted along a line, with a separate line for each observation.

The associated <GEOM_FUNCTION>() is

geom_point(). Here is a dot plot of the mean PM 2.5 levels

for each county in California. We have to first create a tibble

containing the mean levels, and pipe that into ggplot()

neighces %>%

group_by(County) %>%

summarize(Mean = mean(PM2.5)) %>%

ggplot() +

geom_point(aes(x=County, y=Mean)) +

coord_flip()

coord_flip() flips the x and y axes (take it out and see

how ugly the plot is).

The default ordering of the y-axis is alphabetical. We can reorder

the counties based on highest to lowest in mean PM 2.5 using the

function reorder().

neighces %>%

group_by(County) %>%

summarize(Mean = mean(PM2.5)) %>%

ggplot() +

geom_point(aes(x=Mean, y=reorder(County,Mean))) +

ylab("County") +

xlab("PM 2.5")

ggplot() has many additional functions and features that

allow you to adjust the the aesthetic features of your plot. For

example, we can add additional text to your plot to enhance its

readability. To illustrate this, let’s create a scatterplot of mean PM

2.5 and mean poverty rate for each county, but indicate the county

corresponding to each point on the plot. We do this by adding the

geom_text() function.

neighces %>%

group_by(County) %>%

summarize(MeanPM = mean(PM2.5),

MeanPov = mean(Poverty)) %>%

ggplot() +

geom_point(aes(x=MeanPM, y=MeanPov)) +

geom_text(aes(x=MeanPM, y=MeanPov, label = County)) +

ylab("County") +

xlab("PM 2.5")

ggplot() is a powerful function, and you can make a lot

of really visually captivating graphs. You can change colors, add text

labels, layer different plots on top of one another or side by side. You

can also make maps with the function, which we’ll cover a few labs from

now. You can also make your graphs really “pretty” and professional

looking by altering graphing features using <OPTIONS(),

including colors, labels, titles and axes. For a list of

ggplot() functions that alter various features of a graph,

check out Chapter 28

in RDS.

Answer the assignment 2 questions that are uploaded on Canvas. Submit an R Markdown and its knitted document on Canvas by the assignment due date.

This

work is licensed under a

Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Website created and maintained by Noli Brazil